- Rare Cancers Special Issue

- Volume 1

- Issue 1

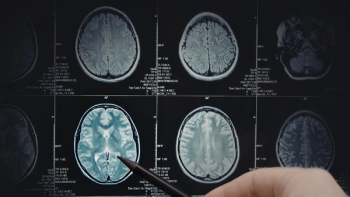

A Rare Opportunity for Patients With Brain and Spinal Cancers

At free NCI clinics, people with some of the rarest disease get tumor analysis, counseling and expert advice.

They have some of the rarest diseases, but people with atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) and other unusual brain cancers report some common experiences.

At diagnosis, their doctors often say things like “You have ATRT. That’s neat — I’ve never seen one of those before. I had to look it up,” reports Terri Armstrong, a senior investigator with the National Cancer Institute (NCI). “It makes patients feel awful. When patients have an opportunity to see experts focused on their disease, it’s a positive experience.”

An NCI program offers that kind of support to adults who have any of 12 uncommon cancers of the brain or spine. The Comprehensive Oncology Network Evaluating Rare CNS Tumors, or NCI-CONNECT, has been funded by the federal Cancer Moonshot initiative for five years. It’s one of several rare-cancer clinics offered by the NCI.

“One of the missions we’re trying to address is that connection — connecting providers like us with centers treating the patients, connecting patients to each other and devel­oping a relationship with advocacy organiza­tions,” Armstrong says.

The brain cancer program hosts twice-weekly clinics at which doctors see patients from all over the country, analyze their tumors, advise them about care and work with their local doctors to make sure they get the most appropriate treatment. Patients looking to switch doctors or participate in clinical trials can be referred to specialists within a network of 33 expert centers nationwide.

Particularly meaningful to patients is that clinic visits give them a chance to meet others with the same cancer types, often for the first time, which is “sometimes emotional,” Armstrong says.

The appointments are free to patients, whether they visit once or regularly. The NCI, which is an arm of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), funds air travel for them and a caregiver and offers stipends toward food and lodging.

NCI-CONNECT helps the NCI and the cancer community as much as it does individual patients. The clinics provide researchers with tissue samples they can study to better understand the genetic mutations that drive these cancers, develop drugs to treat them and establish standards of care. NCI-CONNECT developed educational programs for doctors who want to learn to treat these conditions, and its

Finally, the clinics yield information about the patient experience, collecting details in numbers that would otherwise be difficult to muster due to the rarity of the conditions; about 200 patients have been seen in the clinics since they launched in January 2019. Understanding more about patients’ lives can help doctors improve care for them and others with these diseases, Armstrong says.

Consider, for example, ependymoma, a rare cancer of the nervous system that can occur in the brain or spine. “The dogma in the medical field for patients with tumors in the spine was that you may want to have the tumor removed, because often survival is longer,” Armstrong says. “Over 80% of these patients survive over five years. But we found when we talked to patients that almost 50% of them weren’t able to go back to work because of side effects from the cancer itself, and 75% of them required significant pain medication because of ongoing pain after surgery or from the tumor. It was like a lightbulb for us — it may be controllable for longer, but the impact on the person is so great. This is driving us to realize that we need to understand both the short- and long-term impacts of our care and strive toward improving that care and treatment from the time of diagnosis to reduce or remove effects that negatively affect quality of life.”

Building Rare Cancer Clinics

The NIH offers clinics for patients with rare cancers through other programs, too. Since 2008, a pediatric wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) clinic has been running in Bethesda, Maryland, according to a report on the NCI’s blog, Cancer Currents. Children with GISTs that do not express the two mutations seen in most cases and treatable with approved targeted drugs are eligible to attend the clinic for advice, counseling, tumor testing and meetings with other patients. Their version of the disease, known as wild-type, is considered rare because it does not contain any of this cancer type’s classical mutations.

The clinic, which meets once a year, helped researchers identify the cause of wild-type GIST: inherited mutations in the SDH genes. The researchers also determined that associated epigenetic changes — alterations in the way genes act, without the presence of mutations — can lead to this type of cancer. Finally, they learned that surgery can be avoided, delayed or less involved in many of these patients without producing negative consequences.

That success prompted the NCI to launch a rare cancer clinic focused on medullary thyroid cancer in October 2018. This spring, the first clinic for pediatric chordoma, a rare type of bone cancer, opened. The new clinics are the first efforts of the My Pediatric, Adolescent, and Adult Rare Tumors Network, funded by Cancer Moonshot, according to the blog.

Before they joined the NCI and launched NCI-CONNECT, Armstrong and Dr. Mark R. Gilbert, a senior investigator, chief of the NCI’s Neuro- Oncology Branch and co-leader of the brain tumor clinics, worked together to unravel the mysteries of ependymoma. They tested a regimen that has become a standard of care for people with progressing ependymoma: the chemo­therapy temozolomide plus the targeted breast cancer drug Tykerb (lapatinib).

“We were successful in finding an effective treatment for recurrent ependymoma, in part based on our knowledge of a molecular target,” Armstrong says.

When they arrived at the NCI, she said, the Moonshot funding allowed them to expand that work to encompass 12 rare cancer types.

“The tumor types addressed by NCI-CONNECT were chosen as they represent the rarest of the rare, and because they are cancers we felt we can have an impact in,” Armstrong says. “The most common of our rare cancers (oligodendroglioma) affects about 2,000 patients per year in the U.S., and the rarest, ATRT, affects less than 50 patients a year,” Gilbert adds.

Reviewing and Refining Tumor Testing

When patients visit the clinic, they attend a counselor-led group session on positive coping techniques, including exercise to manage fatigue. They also meet with a genetic counselor to search for inherited dispositions to cancer, as well as a nurse practitioner and a physician who do an exam, review test findings and provide consults.

As part of a first appointment, clinic experts analyze a tumor sample provided in advance by the patient or the treating institution, if one is available. State-of-the-art testing identifies any cancer-driving genetic mutations that may be targetable with medications.

Although patients’ tumors may already have been sequenced by their care teams, the NCI conducts more focused testing than the global cancer mutation panels many institutions use. “We look at mutations and alterations but also methylation (chemical changes to DNA that can alter genetic expression) to classify the tumor,” Armstrong says.

“Providing (tumor samples) is mandatory (for patients), because we do need to confirm the diagnosis,” Gilbert says. “The other part is to have that material for additional purposes. One is if the patient does need a treatment: A lot of personalized cancer care is based on the molecular profile of the cancer, so this has a direct impact for the patient. The other is part of our mission to get a better understanding of the biology of these cancers, and we get a lot of that information from (testing) the tumor tissue.”

The thorough testing has led to changes in diagnoses in over 11% of the clinic’s patients, according to Armstrong, making it more likely that patients will get appropriate treatments. In the remaining cases, NCI doctors are able to confirm the diagnoses, which can be a comfort to patients, Gilbert says.

Patients with more common types of brain tumors are welcome to visit the NCI for consultations, although they will not participate in NCI-CONNECT clinics, Gilbert adds.

Learning From the Data

An important way that NCI-CONNECT collects data to analyze and share is through patient registries — doctors ask patients to supply information.

For each disease type, clinic leaders conduct a natural history study, aimed at understanding the collective patient experience from diagnosis through the course of the illness.

“We collect clinical information and also use patient-reported questionnaires, through which they tell us how they’re feeling,” Armstrong says. “At least once a year, they tell us about their symptoms and overall quality of life. Now we have over 500 people who’ve participated across all the brain tumors, not only the rare ones.”

Those who want to participate but can’t travel can join a web-based outcomes-and-risk study that involves filling out questionnaires. The participants will be asked to visit the clinic if possible, however: “The richness of the information we can get is much greater if they come,” Armstrong says. “It will not only improve what we learn, but they’ll have the opportunity to meet with genetic and health and wellness counselors.

“A main question people ask when diagnosed is: Why did this happen to me?” she continues. “We believe that, by talking to them, going through their history and meeting with a genetic counselor, we can begin to understand (why these cancers develop), because we don’t know that with brain tumors. Smoking and obesity are not factors with these diseases.”

Armstrong and Gilbert would like to see physicians and researchers exploring other types of cancer open similar clinics. “We’re hoping this framework can be emulated by other folks,” Armstrong says. “Our goal is to test the waters, learn the best way to do this and show that (using this kind of model) can improve care and develop treatments.”

Articles in this issue

over 6 years ago

New Therapies Making Progress in Rare Cancersover 6 years ago

Making It Personal With Waldenstrom's Macroglobulinemiaover 6 years ago

Hormones Gone Mad in a Rare Type of Ovarian Cancerover 6 years ago

The Truth About Implantsover 6 years ago

Seeking Immunity: Exploring Kaposi's Sarcomaover 6 years ago

Blowing a Fuse: Fighting NTRK Gene Fusions in Cancer