When Living with Brain Cancer, Life Doesn't Always Go as Planned

How do I plan for life if every nine weeks the path I'm on may have to change? I'm 27 years old and most of my friends have a blueprint. Finish school; stay in their job; get married; and start a family in "X" years. Creating plans is what we're taught to do from the time we're old enough to announce we're going to be astronauts.

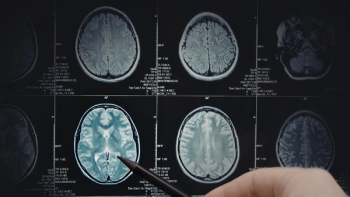

In 2004, at 12 years old, I was diagnosed with a brain tumor: an oligodendroglioma located in the area of my brain that controls movement in my right side. After an aggressive surgery, months in the hospital and years of recovery, I felt confident creating plans to follow my passion for ocean conservation and a life of service.

I went to college, became an EMT, advocated for climate change action, joined conservation efforts in Madagascar, sailed a tallship through the high seas, and after college received a fellowship to work in Indonesia. I wanted to be an environment and health leader to improve the lives of those around me. I had worked diligently to make this path possible, but after a year and a half abroad in Indonesia, I had my first seizure in 10 years.

I went home to celebrate Thanksgiving and undergo an MRI to determine the cause of the seizure. I was 24 at the time, waiting in Boston Children's Hospital with my mom. As kids played with toys and coloring books around me, my heart raced - the feeling the cancer community calls "scanxiety." I yearned to return to Indonesia, but none of it went as planned.

On November 24th, 2014, I was diagnosed with a recurrence. Despite the friendships and work I'd left in Indonesia, I couldn't go back. I was immediately derailed, living back home with my mom.

Within minutes of a conversation with my doctor, my perspective on life, my relationship to time, and my sense of mortality all changed.

The tumor was too dangerous to remove surgically, so I underwent radiation and chemotherapy. Throughout this year of treatment, I couldn't help but start planning again. And yet my life had changed fundamentally. It was now a matter of "when", not "if" the tumor would come back. How was I supposed to move forward with this uncertainty? My life would likely be shorter than I expected, forcing me to reconcile what was most important to me: Presence and human connection. These values needed to serve as the roots for whatever I did next.

Since before my recurrence, I had thought about becoming a physician to live my values every day. Despite the future-oriented nature of the education process, I held onto hope that my treatment would give me another five, 10, maybe even 20 years until my tumor grew again. I had a plan: Become a doctor to combine human health with my passion for environmental health.

At 27 years old, I took a risk and moved across the country to California for medical school. I transformed from a patient to medical student and joined a cohort of passionate classmates dedicating their lives to service. I felt incredibly lucky, but not even a year had passed when everything changed again.

My tumor grew back.

"I can handle this," I thought. I'd take the summer to undergo surgery to remove a section of the tumor, and then continue with my studies as I underwent treatment.

However, a couple of weeks following my surgery, I learned the remaining inoperable section of my tumor had evolved into a more aggressive form of cancer. There was no standard of care or clinical trial I could fit into.

This wasn't the plan.

I returned to school part-time and started an experimental targeted therapy.

It didn't work.

We changed our approach: Radiation for 10 days followed by indefinite immunotherapy infusions every three weeks. Scans every nine weeks.

For the first time in my life, I didn't know how to plan. I could set a goal, but in nine weeks it might be disrupted. In addition to this existential dilemma, I faced the practical hurdles of treatments and side effects.

Some may say that we all live with uncertainty; at any moment we could get hit by a bus.

That may be true, but those with cancer live in a different world. A world where time is tangible. As a 27 year old with inoperable brain cancer, my timescales are vastly different than my peers'. A day feels like a week, a week might be a month, and a month has become a year.

To experience time in this way is a blessing and a curse. Every decision carries more weight because time is limited, and I don't want to waste it. The only option I have is to focus on the present and live my values.

It's the best plan I have.