Pushing Glioblastoma Awareness Toward A Happier Ending

In honor of the second annual Glioblastoma Awareness Day in the United States, Erica Finamore shares her story of the journey and untimely passing of her husband Jon Marc. But how that passing has still given to the research of brain cancer.

On February 25​, 2018 I was 28 — a newlywed working at my dream job at Food Network Magazine. My husband, Jon Marc, also 28, was my college sweetheart, and a neurology resident at NYU. Jon had always wanted to go into neuroscience​. ​His grandfather had suffered from Alzheimer’s and he had always been fascinated by the way the brain worked — an organ so important that it not only controls our functions but who we are as people.

That morning our lives were fairly standard and perhaps a little boring and we were starting to talk a bit about when we’d buy a home or have children. But by that night, nothing about our future was certain, or as I later learned, possible. It had been a few weeks of headaches and memory loss for Jon when we went to the emergency room at Mount Sinai in New York.

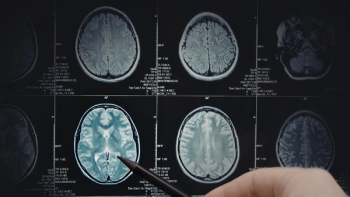

We assumed we were both just being overly anxious, but better safe than sorry. A test that night showed that Jon had a large mass in his brain — it was big, it was deep, and it didn’t look good. A biopsy later confirmed that it was glioblastoma, a highly aggressive and lethal brain cancer. I didn’t realize at first just what we were facing, but Jon did. As a neurologist, he had seen patients receive this grim diagnosis, and after our first appointment with the neuro-oncologist, Jon was unfortunately wise enough to tell me, “I had forever and now I don’t.”

Those words broke my heart then and they still shatter me now. They seem impossibly cynical but they’re true, because people diagnosed with glioblastoma face a harsh reality that treatment options are limited and weak, and that a cure isn’t quite in sight yet. When Senator John McCain passed from glioblastoma back in 2018, news media rushed to talk about the ways in which we were getting closer to a cure, to put a positive spin on it. As humans, we’re always desperately looking for an upside to any situation. After Jon’s first resection surgery to debulk the tumor, friends would ask me if they got it all, if he was in remission, if it was over now. They didn’t, he wasn’t, it wasn’t.

Jon was never quite the same and he never returned to work — his lifelong passion — or really got to be his full, independent self again. Glioblastoma does not have a “feel-good” component, and there’s very little hope for a life after it: Only 6% of patients live past the five-year mark, and the average patient only lives 12 to 18 months. Despite the work of scientists and doctors alike, patients with glioblastoma face the same odds they did more than two decades ago, with virtually the same treatment options given in the 1990s. That’s right, there’s been no tangible progress since “Fight Club” came out.

If patients are lucky, they are candidates for a life-threatening and possibly personality and capability altering surgery that can remove some of the tumor. We celebrated the chance to have a surgery in which there was a 50% chance Jon would lose his peripheral vision, a 5% chance he would never intelligibly speak again, and a small chance he wouldn’t make it out at all. After this, the diagnosed are treated to a cocktail of daily chemo and radiation, which works only to try and extend the life of the patient and is only effective for a small fraction of them.

Some will elect to try a tumor-treating field device that they must wear on their back that sends electrical pulses to pads placed on the patient’s scalp. This is as far as we’ve come with standard treatment options. Jon, even with aphasia after his surgery, knew that our best shot was a clinical trial — an experimental study where he would try a new drug or procedure and we’d pray that this was the cure and that Jon was patient one. If Jon had been diagnosed in 1999, this would have been our same, best option. For over two decades, each patient with glioblastoma has hoped and prayed to be that patient zero.

For over two decades thousands of men, women and children have confronted the devastating fact that they were not patient zero. They weren’t close. Jon passed away in April, 26 months after diagnosis. I lost the greatest person I’ve ever known, but the world lost a compassionate, kind and driven doctor who would have made a huge difference in the lives of thousands of people suffering from neurological disorders. I’m fully aware of how ironic it is that a brain doctor got brain cancer, but I know that even in death, Jon is moving the field forward.

Someday, someone will tell this story, but their ending will be happier than ours. I look forward to that day with everything in my being, but we have a long way to go and a lot of work to do to get there. This might sound flippant, but we would never put up with using a computer or phone from the 1990s, so we clearly can’t be complacent about treating people with the same methods we used the year Napster first launched.

With the world in flux right now, it’s easy to forget that there are other urgent problems, but there are, and this is one of them. Every moment our leaders and ourselves aren’t pouring everything we have into research and treatment, another person is gone; another family feels helpless and hopeless. In a world where our leaders are doubting the importance of scientific advancement, we need to be louder, stronger, and more aggressive. We can’t lose more people like Jon; the world just can’t afford it.

Wednesday marks the second annual Glioblastoma Awareness (GBM) Day in the United States. Erica Finamore is participating in the National Brain Tumor Society's virtual GBM Day commemoration.