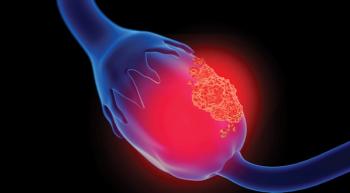

Ovarian Cancer

Understanding ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is difficult to diagnose early because there is no good screening method to detect it, and its symptoms often mirror those that might arise as a normal part of the menstrual cycle or with other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome. This means that most women with ovarian cancer receive their diagnosis after the disease has reached advanced stages. One in 78 women will get ovarian cancer, making it a rare disease.

WHAT IS OVARIAN CANCER?

Cancer arises when cells begin to grow out of control. Historically, ovarian cancer was thought to begin in the ovaries, but it is now known that this disease type also includes primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers, because it can start in those areas, as well.

Three types of cells can lead to separate subtypes of ovarian cancer: epithelial, germ cell and stromal. Up to 90% of malignant ovarian tumors are epithelial, which has four subtypes: serous carcinoma (the most common), clear cell carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma.

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS FOR OVARIAN CANCER?

Being postmenopausal is a risk factor for ovarian cancer, as is older age. Having a first full-term pregnancy after age 35 or never carrying a pregnancy to term is also associated with a higher risk. Taking estrogen without also taking progesterone for five to 10 years after menopause can also raise risk.

Family history is another important factor. Women with family members who have ovarian, breast, colorectal and certain other cancers, as well as women who have a personal history of breast cancer, may be at higher risk of ovarian cancer. Women who have inherited mutations in specific genes, including BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, RAD51C/D and the Lynch syndrome genes are at higher risk for ovarian cancer.

While some women have an inherited risk of ovarian cancer, most ovarian cancers are due to mutations in ovarian, fallopian or peritoneal cells that a woman acquires during her lifetime. The causes of acquired mutations associated with ovarian cancer remain unknown. Acquired mutations may occur by random chance over a woman’s lifetime. Study results are not clear about the role of other factors, such as being obese or using in vitro fertilization drugs, as potential contributors to the development of ovarian cancer. Breastfeeding and using birth control pills can lower the risk of ovarian cancer.

WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS OF OVARIAN CANCER?

The most common symptoms of ovarian cancer are bloating, pelvic or abdominal pain, feeling full quickly when eating and having to urinate more urgently or more often. Other symptoms include fatigue, back pain, pain during sex, upset stomach, constipation, changes to bleeding during the menstrual period and belly swelling accompanied by weight loss. In many cases, these symptoms do not indicate ovarian cancer. However, if you have any of these symptoms, it is important to get them checked out by a doctor if they are a change from your normal experience or occur more than 12 times in a month.

HOW IS OVARIAN CANCER DIAGNOSED AND STAGED?

No screening test for ovarian cancer is considered accurate enough to use on the general population.

A manual pelvic exam can reveal a number of health problems but is likely to miss many ovarian cancers.

Those at high risk of ovarian cancer may be screened with transvaginal ultrasound, which can find a mass in the pelvis but not determine whether it is cancerous. A blood test for elevated levels of the cancer antigen (CA) 125, a protein, is useful in women known to have ovarian cancer but is not an accurate way to diagnose the disease. High CA-125 levels can occur in people who have conditions unrelated to ovarian cancer, and tests for this antigen can miss people with ovarian cancer who don’t express a lot of this protein.

If screening or symptoms suggest ovarian cancer, a doc- tor will use imaging to look for a tumor. This can include CT, MRI or PET scans or laparoscopy, in which a thin, lighted tube is threaded through a small abdominal incision to send images of the ovaries and other pelvic organs to a video monitor.

If a mass is found, a piece will need to be removed (biopsied), usually surgically, and then analyzed in a lab. If ovarian cancer is present, it will be given a stage ranging from 1 (indicating that the cancer hasn’t spread beyond the ovary) to 4 (indicating that it has spread to distant parts of the body). These cancers are also assigned a grade of 1 through 3 or classified as low grade or high grade to indicate how different from normal the cancer cells are. High-grade cancers are more likely to grow quickly and spread.

When ovarian cancer is diagnosed, the patient should undergo genetic testing using blood or saliva to find out if an inherited gene mutation is the cause of the disease. This information can help guide treatment, alert a woman that she should be screened for additional cancers and make family members aware that they might also have an inherited predisposition to cancer.

HOW IS OVARIAN CANCER TREATED?

Epithelial ovarian, germ cell, primary peritoneal and fallopian tube cancers are treated the same way regardless of stage: surgery followed by chemotherapy. Stromal tumors are treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy or hormone therapy.

In most cases, the surgery removes the tumor, or as much of it as possible, plus the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Chemotherapy is sometimes given directly into the abdominal cavity rather than by infusion into the bloodstream through an arm.

If a woman isn’t well enough to undergo surgery, she may get chemotherapy first and then have surgery when she is able. In some cases, if the cancer has spread far beyond the ovary — for instance, to the liver — chemotherapy may be given before surgery to shrink the cancer and make surgery easier.

In later-stage disease, surgery may involve removing the lining and boundary tissues from inside the upper abdomen, as well as parts of the intestines, liver, bladder or gallbladder.

Maintenance Therapy for Ovarian Cancer

Maintenance therapy is a type of treatment given after chemotherapy has been completed to try to keep the cancer from returning. The goal of maintenance therapy is to extend the length of time before the cancer returns or even to turn a temporary remission into a long-term cure.

Two types of drugs — PARP inhibitors and the targeted drug Avastin (bevacizumab) — have been Food and Drug Administration-approved for use as maintenance therapies in women with advanced ovarian, fallopian tube and primary peritoneal cancer if they have an inherited or tumor mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 or if the ovarian cancer has a tumor feature called homologous recombination repair deficiency, or HRD. A relatively new type of ovarian cancer treatment, PARP inhibitors are oral drugs that block an enzyme known as PARP that cells use to repair DNA damage. Clinical trials of other PARP inhibitors or new therapies may also be an option for some patients.

Treatment for Other Types of Ovarian Cancers

Germ cell tumors are also treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy. Stromal tumors are treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy or hormone therapy.

WHAT ARE THE POTENTIAL SIDE EFFECTS OF TREATMENT?

Women who were not in menopause before surgery for ovarian cancer will experience it afterward, which can bring on symptoms including hot flashes, sweats, fatigue, and skin and vaginal dryness. There are treatments available to alleviate some of these symptoms. Younger women also may experience distress over their loss of fertility following surgery.

Some women whose lymph nodes were removed may experience lymphedema, a pooling of fluid in nearby parts of the body.

Chemotherapy for ovarian cancer can cause hair loss, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea and/or constipation, and tingling or weakness in the extremities. It can also result in fatigue, a feeling of brain fog and low blood counts that can lead to infection. PARP inhibitors can cause fatigue, nausea and low blood counts.

HOW DOES OVARIAN CANCER AFFECT A PATIENT’S LIFE?

Patients with ovarian cancer that has spread to other parts of the body can experience remission after treatment but are likely to face a recurrence that requires additional therapy. This can cause worry and disappointment. Women who were not in menopause before surgery will experience it afterward, which can be a big adjustment.

If a woman finds out that her disease stems from an inherited gene mutation, it could mean she is predisposed to other kinds of cancer and should consider more frequent screenings or preventive treatment, such as lifestyle changes, medicine or surgery. Patients with inherited predispositions to cancer are encouraged to share that information with family members so they can seek genetic testing and counseling.

WHERE IS HELP AVAILABLE?

Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered (FORCE) is a non-profit organization dedicated to improving the lives of people affected by inherited cancers. It offers a wealth of information about hereditary cancers, a search engine to help patients find clinical trials, and support services including personalized guidance and a help line (facingourrisk.org; 866-288-7475). Also remember to check our list of resources online at curetoday.com/journey.