Cultivating Symbiosis

During her cancer journey, an author and her physicist friend traded insights.

Editor’s Note: This piece was submitted by a contributing writer and does not represent the views of CURE Media Group.

For most people, the term “physicist” evokes images of a white-haired, bespectacled mad scientist in a lab coat or a nerdy “Big Bang” character with a bowtie and a pocket protector. I never thought I’d become friends with one — much less have one truly impact my life. But everything changed when I was diagnosed with cancer.

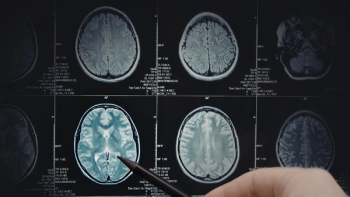

In 2015, I noticed that my field of vision was decreasing and I couldn’t see out of the corners of my eyes. Doctors brushed it off, telling me it was probably fatigue or to just “drink more water” — until I literally walked into a door frame in one of their offices. I was diagnosed with a stage 4 glioblastoma, the most advanced and aggressive form of malignant brain tumor.

I was initially given a year and a half to live. But I was determined: I was young. I was healthy. I would be an outlier and not a statistic. So, I faced my circumstances head-on (literally) with a brain surgery two weeks after my diagnosis. I underwent chemotherapy, but the tumor continued to grow, so radiotherapy was recommended. The daily radiation and chemo regimens were exhausting, debilitating and terrifying, and I missed work for an entire year. Stuck in the hospital, I began writing my thoughts down in a journal as a way to help document the journey and process my emotions. As the diary became longer and longer, I saw the potential to transform it into something that might help others, and that’s how my book, “Life Happens,” was started.

The book is a work of fiction infused with my own personal experiences, and it reflects, in detail, what I underwent during my treatment process: the ins and outs of hospital visits, surgeries and radiotherapy procedures, along with the challenges of coping with my own mortality. I intended the book to offer readers a front-row view of the daily experiences and struggles familiar to many cancer patients but often hidden from society and even from the innovators advancing new cancer treatments. It reveals the fears we face as we enter a radiation therapy machine, when we wake up from surgery, as we wait on unknowns and uncertainties. I wanted my writing to provide valuable insights for other cancer patients and for the many physicians, researchers and physicists striving to find new treatments and potential cures for this disease.

This is where my friendship with a medical physicist became important. I first met Paul Naine at a party in 2013, when I was still happily unaware of my condition. Paul is a medical physicist (yes, they do go to parties!) at a company that manufactures oncology devices and radiotherapy machines for people with cancer or brain disorders, much like the one on which I was treated. As a medical physicist, Paul is a critical part of the process through which innovative radiation therapy research is translated into devices and systems for clinical use. He took me under his wing when I moved from Sweden to America, where I went to work as an intern. He helped me acclimate to a new country, introducing me to his friends and to the Atlanta, Georgia, area. A year later, after I had moved to Dublin, Ireland, our conversations looked a bit different, as he was now helping me navigate my cancer experience.

I spoke with Paul often about my diagnosis and treatment plans, and through it all, he was exceedingly supportive and helpful. He told me about side effects and reassured me that it was normal to feel tired and to lose hair. It was helpful to have someone professional to talk to besides my radiologist.

Though he worked in this field professionally every day, this was now personal for him. I told him how the face mask used to immobilize my head and the small enclosure of the radiation therapy machine made me feel like I was in a sci-fi movie, and how I wished the doctor had been more candid with me about what to expect. Paul deals in the math and science of cancer, but my battle with the disease emphasized that there is also a human component to these calculations. While the patient experience was something that he had always tried to keep top of mind, seeing it through my eyes reinforced his commitment to ensuring that the end product of his work wasn't just a machine, but an opportunity for hope for those fighting cancer.

Paul had his team read my book as a reminder of how important it is that radiation devices are developed to improve patients’ lives. It helped give them new insight into what it’s like to undergo treatments in the machines they deploy and calibrate, and emphasized the importance of making the patient the priority in their professional work.

I hope to continue to inspire people — whether they are patients themselves or those working to improve our care. It is essential that we pursue cancer treatments that address and cure the soul as well as the body. Life happens — and it is our friendships, our fortitudes and, in my case, a physicist, that make it all worthwhile.

Caroline Reber recently succumbed to glioblastoma. She was a marketing strategist who penned a novel based on her cancer journey. The book, “