Publication

Article

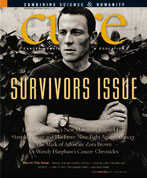

CURE

Patience & Strength

Author(s):

Profile of Lance Armstrong and discussion of his book, "It's Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life."

The climb to the top for Lance Armstrong began in trendy Plano, Texas, a suburb of Dallas and not a place where a slight kid without money to spare would stand out. In Texas high schools, where football coaches often make more than the principal, football was, and still is, king. For Armstrong, this meant focusing his determination and unflappable self-confidence on other areas: swimming, running, and cycling.

At age 12 he rode his bike 10 miles to swim 4,000 meters at the city pool before riding his bike to school. At the end of the day he did it in reverse, swimming another 6,000 meters before riding home. By age 14 he was competing in triathlons across the state.

“What makes a great endurance athlete is the ability to absorb potential embarrassment and to suffer without complaint,” Armstrong explains in his 2001 memoir, "It’s Not About the Bike: My Journey Back to Life". "I was discovering that if it was a matter of gritting my teeth, not caring how it looked, and outlasting everybody else, I won."

Armstrong also had a secret weapon—his mother, Linda Armstrong Kelly, whose own personal determination provided her son a role model and personal assistant who drove, organized and cheered during those early years.

By age 16 Armstrong earned $20,000 a year winning triathlons; by his senior year of high school, he was winning cycling and triathlon events across the country. After graduation, while his friends left for college, Armstrong was named to the U.S. national cycling team and left for Europe.

The years that followed took Armstrong all over the world, where he was accompanied by words like cocky, impatient, arrogant, and angry. He wouldn’t play by anyone’s rules but his own, and that was to put his head down, pedal, and win. “In a long stage race, you give a little to make a friend, because you might need one later. Give an inch, make a friend. But I wouldn’t do it,” Armstrong recalls in "It’s Not About the Bike." "Partly it was my character at the time: I was insecure and defensive, not totally confident of how strong I was. I was still the kid from Plano with the chip on my shoulder, riding headlong, pedaling out of anger." And not caring if he wasn’t liked, as long as he won.

By 1995, Armstrong had matured as a cyclist and a man, learning that the headlong rush may not be the best approach. That year, he finished the Tour de France for the first time, returning to his adopted home of Austin, Texas, with a new trait he says is the “defining characteristic of a man”—patience.

In fall 1996, after ignoring symptoms for months, Armstrong made an appointment to determine what was causing one of his testicles to swell. The answer came on October 2, 1996: advanced stage 3 testicular cancer.

Armstrong attacked the cancer with the same determination he used when he rode, seeking out the best physician and treatment that could help him return to cycling. He found it at the Indiana University Medical Center in Indianapolis, where Lawrence Einhorn, MD, had developed a regimen that took testicular cancer from a deadly disease to one that could potentially be cured. Armstrong underwent arduous treatment for three months, finishing in December 1996.

He came to think of himself as a cancer survivor first and an athlete second, founding the Lance Armstrong Foundation in 1997 because, he says, “Too many athletes live as though the problems of the world don’t concern them.”

With urging from friends and family, Armstrong found his way back to the bike, and by fall of 1998 he was winning international races with a new team and a new body, resculpted after chemotherapy and tempered by pain.

In 1999 cancer survivor Lance Armstrong won the Tour de France for the first time, a feat he repeated for the next six years—winning seven times in a row—giving cancer survivors everywhere a new hero.